Environmental Perspectives episode 3

Notes from the field

What keeps entire ecosystems running while we’re looking the other way? Source: Andrea Cassani / Unsplash.

Desperation surveys: when the weather forces you to look at the really important stuff

A Bioblitz event is meant to be a celebration of the boundless variety of life, when butterflies come out in the sunshine, are eaten by hornets (or birds), lizards bask on spectacular fungi, and everything is beautiful and draws the visitors in. Sometimes, though, the weather doesn't play nicely. Our visit to a site near Llandeilo was looking a bit bleak from the start: thunderstorms were predicted, rain was starting early, and none of the public visitors turned up. Can't really blame them, but still... it puts a bit of a dampener on things!

The problem with rain is that most diversity is in the form of insects, and most insects really don't like rain. If you're an entomologist, like me, it's a perfect excuse to avoid going out in the rain: the insects won't be flying, and especially all the larger, charismatic critters will be staying in nice sheltered nooks and crannies and refusing to come out. This is a problem if your goal is to build up a nice, long species list and please the crowds.

Sometimes, though, we're forced down a different route... and that can be when things get really interesting. When most of the big, glamorous bits of biodiversity are hiding, we need to focus on the smaller majority: the things that we barely notice most of the time, but which serve to underpin the entire ecosystem. Many of these groups are obscure, tiny (often just 1–2 mm or less), and very hard to identify. In most bioblitzes, where the goal is a long list of species, we tend to ignore the things that simply can't be identified without an expert and a really big microscope. Being forced into paying attention to them, like on this particular day, can be a very good thing.

The Soil Multitudes: Mites, Springtails, and the Microscopic Engine Room

If we lose what lives in the soil, what else comes crashing down with it? Source: Joe Botting

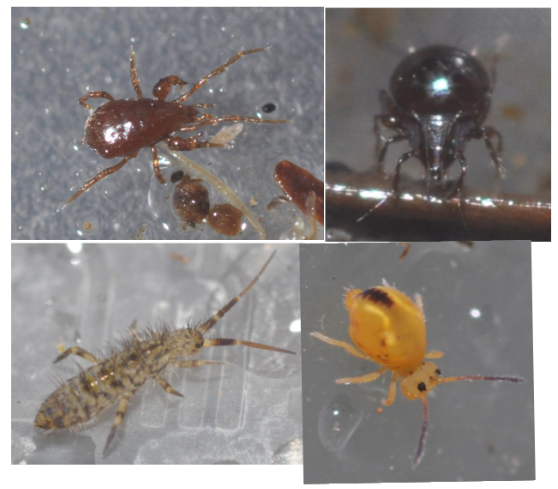

Let's start with the soil. Everyone knows about earthworms creating the soil, but they're actually not the most important component: they're far outnumbered by springtails and mites. Springtails, in particular, are hugely abundant decomposers that turn organic material into soil and help to create the structure of the soil in the process.

There are several hundred species in the UK, and a few of the larger ones can turn up by looking under logs, stones, and the like. Some of them are identifiable with a big camera, but others need examination of minute details in a compound microscope. They are, though, exceedingly cute. They're not technically insects, but rather are a sort of distant cousin: they have six legs (plus a vestigial pair that they jump with) but no wings.

Maintaining an ecosystem needs more than just one component, of course, and that's where mites come in. Thousands of species live in UK soils, and most of them are virtually unknown. Hardly anyone can identify the species, which is a very specialist job involving microscopes and a library in multiple languages, and as a result, there are numerous species in the UK that nobody has yet found or identified.

Some of them (especially the remarkable oribatids) break down organic material into soil, like springtails... but they live for several years, and produce only a few eggs during their lives. Others, like the mesostigmatan Pergamasus, with its inflated, spiny second legs in the male, are active and voracious predators, keeping the populations of springtails, nematodes and other small, soft invertebrates in check.

We still know very little about the diversity of mites living in soils across the UK, and hardly any records have been made of particular species. Nonetheless, even taking note of a few of the things scuttling around under your camera can reveal a truly fascinating world, and show us how much we're missing.

How do you grow a forest without the engineers underground? Source: Joe Botting

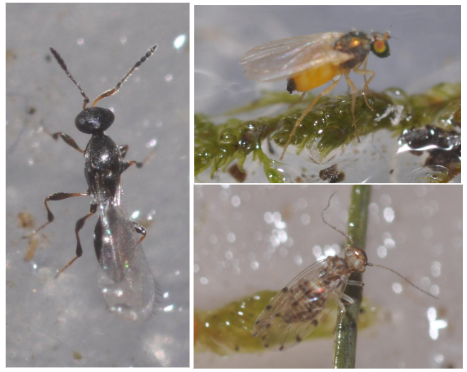

Forests Within Forests: Tiny Lives in the Canopy and Bark

It doesn't get any easier when you go above ground. Native trees like oaks famously support hundreds of other species, right up to the ones that most people notice (e.g. birds). However, do they manage that, though? With an intricate, complex system of parasites, herbivores, predators and others, most of which go completely unnoticed by almost everyone. At one point, we took shelter in some mature woodland next to the site and found some low-growing twigs growing from the mossy bark. Knocking a few leaves into a box revealed all sorts of minute and critical parts of the ecosystem.

Springtails feed on the algae and lichens and are hunted by mites and harvestmen. Barkflies also feed on the mildews and algae, preventing the bark from being swamped by those growths. These, in turn, are prey for a range of small predators, from flies to beetles. The tree itself is attacked by parasites: gall wasps and cecidomyid midges, which induce growths on the tree's leaves or twigs (they don't really harm the tree, but provide shelter for the insect larvae).

Those, in turn, fall prey to parasitoid wasps: the most diverse group of insects in the UK, with some 9000 species. Each species tends to have a specific species of prey, in which the larvae devour the larvae of its host, and some of those are beset by other wasps, which we call hyperparasitoids... and so on. These metallic marvels, like chalcids and braconids, are beautiful to see, but practically impossible to identify, and their rather grim habits eventually persuaded Darwin that there couldn't be a benevolent creator. Larger relatives, the ichneumons, search for caterpillars in the undergrowth and are responsible for the world not drowning in moths. They're really rather important.

Isn’t it time we looked down instead of always up? Source: Joe Botting

Even though we didn't have a very long species list from the site on this particularly soggy day (a mere 95 species!), we did meet quite a few of the creatures that would otherwise have gone overlooked. Opening our eyes to what we can't identify can reveal a great deal more about the workings of nature and make us alert to things that we can't afford to ignore. When we record a treecreeper (or when we don't!), it is a question of whether there is enough food to support them.

For them, food is insects or other invertebrates, and the entire web of smaller organisms is too often ignored. Each of these organisms has a complex life and behaviour, and is extraordinary when we actually take the time to look at them. Although generally humans don't see them, they're what make the entire ecosystem work; when there are problems, we don't tend to notice them until they affect the bigger things at the top of the food chain. It's about time we all paid attention to these smaller neighbours, because without them we simply can't understand the world around us...

By Joe Botting